Core Values

The core values of this National Clinical Programme are:

- Working in partnership with service users

- Comprehensive skilled assessment

- Evidenced based care and treatment

with the overall aim of providing “strategies for coping in addition to medication, thereby enabling the person to obtain developmental and structural gains that would not otherwise be possible” (Caddra, 3rd Ed. 2014).

In this way people learn compensatory strategies and skills to enable them cope with the negative aspects of ADHD.

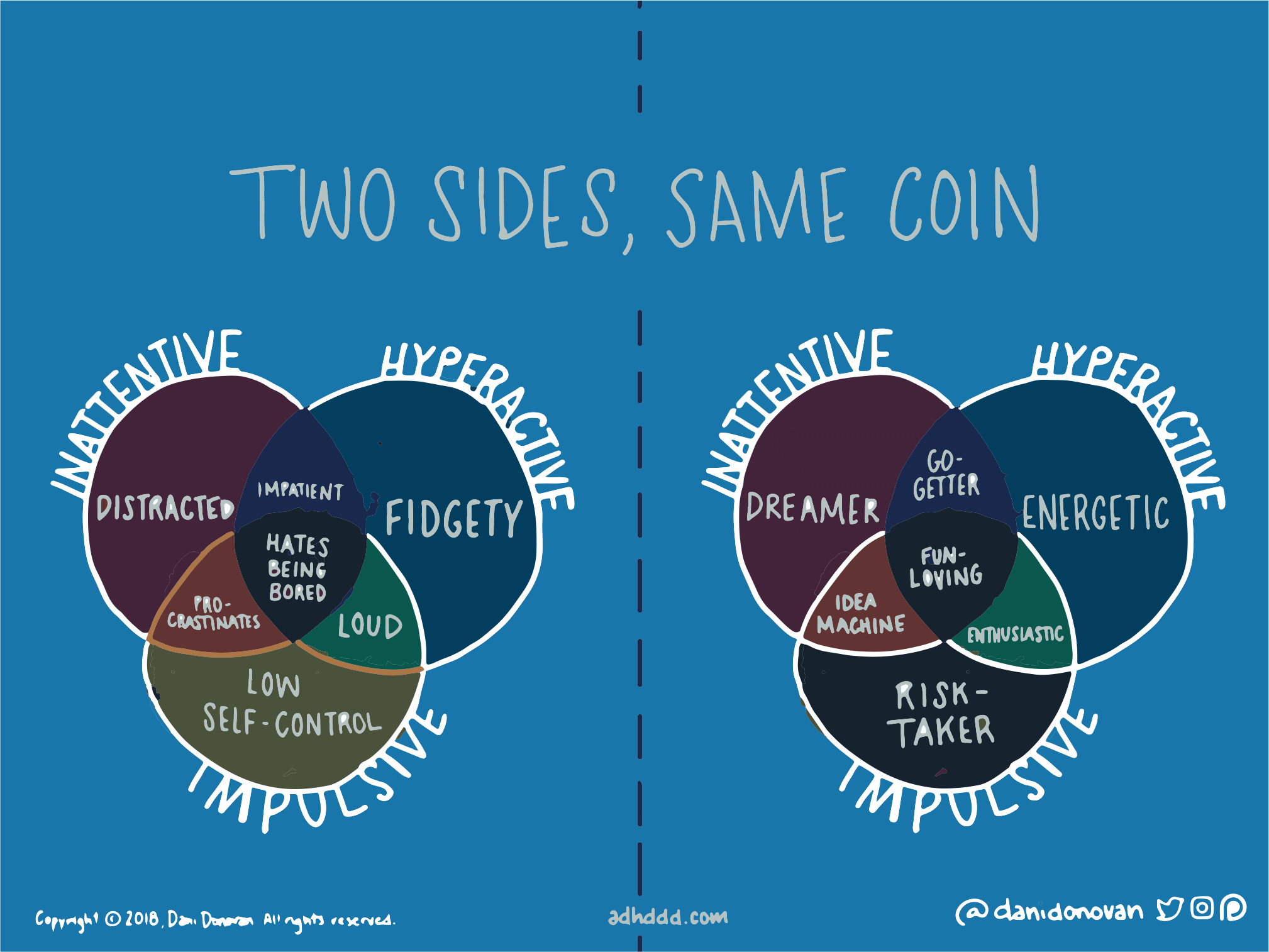

Conceptually ADHD may be viewed as an altered ability, rather than a disability. For people negatively impacted on by their ADHD, the value of diagnosis and tailored made interventions is to support them in acquiring the skills to overcome any associated negative impacts whilst maximising the positive features of ADHD. This is in line with A Vision for Change (2006) requirement of involving service users at every level of service provision. This includes an active role in diagnosis and in decision-making on treatment and developing the capacity of service users to do this.

The core value of service user centrality permeates this Model of Care.

It is in part based on a presentation given by the Working Group’s service user nominee from ADHD Ireland the key points of which are outlined in the next section. It is important to highlight the positive aspects of ADHD and the subsequent section describes these.

Stigma against adults with ADHD is a very real phenomenon and is also addressed. Finally, the guiding principles or rules derived from the core values are listed with particular reference to their role in underpinning the Model of Care.

Service User Perspective

This section provides a unique perspective based on information from adults living with ADHD and the challenges it imposes. Reports were collected informally, for this Working Group and for service development, from service users within ADHD Ireland and from an online adult ADHD support group.

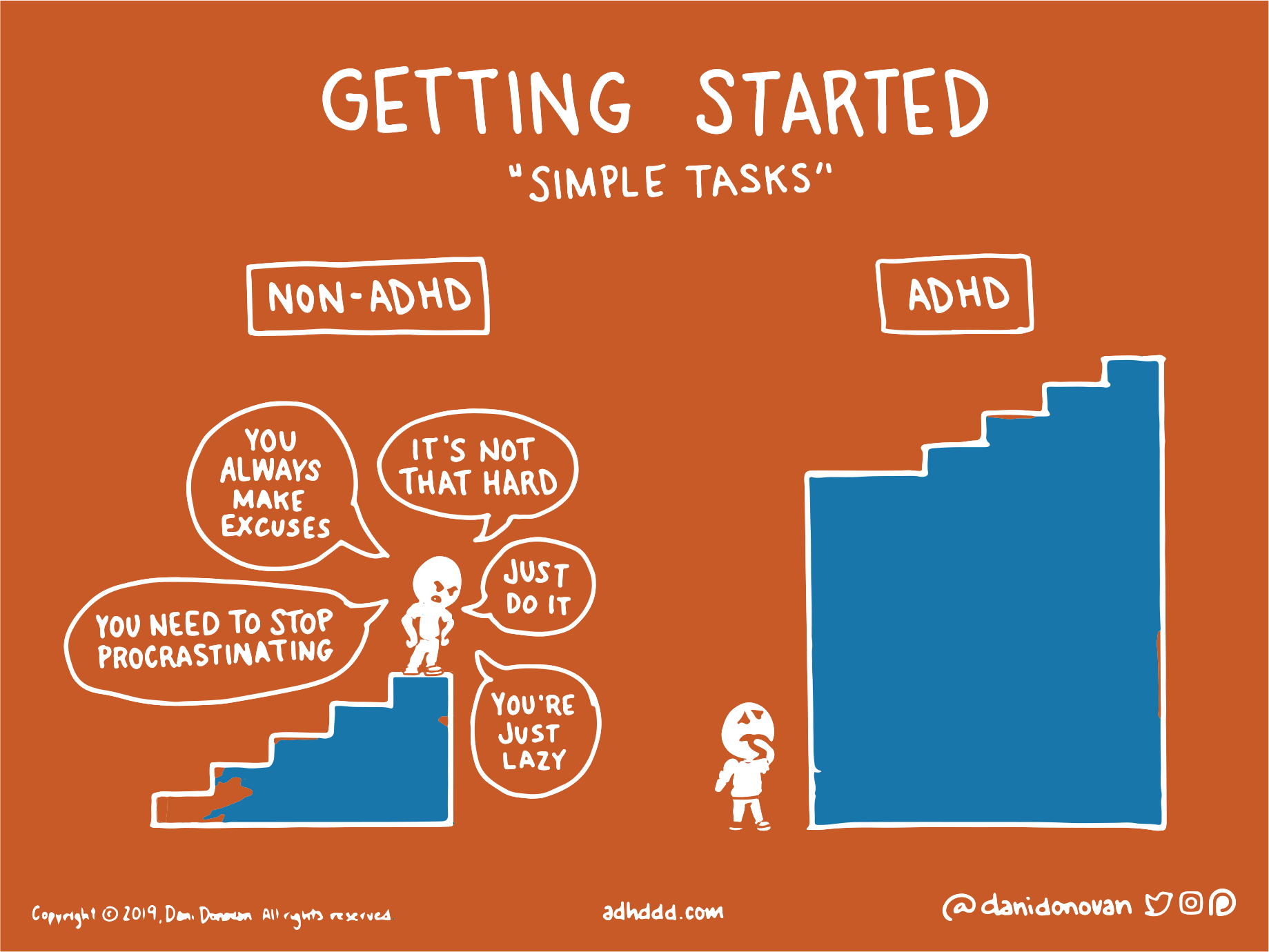

According to service users, ADHD is associated with a wide range of everyday difficulties at home, including day-today tasks such as housework, time management, organisation and paying bills but also in relationships with family dynamics often contributing to chaotic and volatile lifestyles.

In addition, challenges in work such as forgetfulness, poor time management, impulsivity and difficulties managing relationships occur.

Psychosocial difficulties were also identified including relationship problems (colleagues, family, friends, etc.), feelings of depression, anxiety, stress and exhaustion.

Adults with ADHD reported that the journey to diagnosis was extremely difficult with gaps in services, especially public services, meaning that they often had to attend private services. In interacting with professionals, the adults experienced frustration describing problems such as some professionals’ lack of knowledge about adult ADHD (especially its diagnosis in adulthood) and a perceived lack of empathy. They often felt not heard, understood, listened to and sometimes not believed.

Delays in diagnosis were reported as widespread.

However, the merit of having a definitive diagnosis was highlighted by adults and they advocated for early diagnosis to avoid the problems of living with undiagnosed ADHD. Adults reported relief when diagnosed and the importance of then developing self-awareness, accessing support and education. Nevertheless, a diagnosis may also be challenging for adults to come to terms with and anger with a late diagnosis may accompany the relief (Carr-Fanning 2015).

The advantages of receiving a diagnosis and the difference it can make were reported by a 32 year old woman in a study by Carr-Fanning (2015):

I think getting myself diagnosed has been a big thing.

Because I’m only newly diagnosed. It’s funny because when I went out and told people they, the whole pub, just laughed, and all my friends were going "you seriously didn’t know? We’ve known for years!".

And I was thinking ‘why didn’t they tell me?’ Some people just thought I was a social butterfly, but it was more a wasp on acid.

You know I was out the other night and my friend said ‘you’re hyper, you’re just not manic anymore … which is just your personality’. So, she said that’s still there, you’re just not the extent of madness, you’re able to sustain a conversation now.

Following diagnosis adults reported inadequate treatment services for adults with ADHD in Ireland and that services are always private and can often be costly.

Support with disclosure of a diagnosis of ADHD, especially to employers, was also suggested in this study. Some of the adults wondered whether there are any benefits to making a disclosure, worrying that they would not receive any support. Also, whether it could have negative consequences with stigma and scapegoating and being blamed for things that go wrong.

Another issue commonly reported was the presence and impact of stigma when professionals and other people (including family members) do not accept ADHD as a legitimate diagnosis. As a result, people with ADHD may often feel they have to fight for recognition as having a disability because it is hidden and often discredited.

Adults with ADHD highlighted the importance of recognition of ADHD as a legitimate diagnosis and the need for attention to the use of appropriate language.

Conversely some adults may object to being labelled as “disabled” or “disordered”. Similarly, the construction of people with ADHD as “suffering” may be objectionable to some as are derogatory and degrading words such as “lazy”, “crazy” or “weird” used in association with ADHD.

Based on service users’ reports, adults with ADHD need:

- Access to publicly funded services that provide diagnosis and treatment (a range of treatments including, but not limited to, medication)

- Psycho-education

- Practical training, education and supports (e.g. practical life skills, home, work, friends, etc.)

- Peer support groups

- Online fora

- Digital aids and educational materials

- Support for family and spouse/partner

- Reduction in stigma

- Recognition for ADHD as a legitimate diagnosis in adults

- A focus on strengths and positive attributes that may be associated with ADHD in adults

In conclusion, adults with ADHD emphasise that:

- ADHD affects all aspects of a person’s life.

- In terms of clinical guidelines, people with ADHD emphasise the need for diagnosis and treatment (multi-modal treatment)

- Service users being participants in the diagnosis and treatment process

- The need to combat stigma

- The need for clinical services to work in partnership with community-based organisations, CAMHS (when transitioning to adult services), higher education and employers.

Positive Impacts of ADHD

Whilst not always recognised because of the at times overwhelming challenges associated with ADHD, there is equally an association between ADHD and inherent skills. These bring a richness and creativity on a personal, social and economic basis as evidenced by the very many now well known successful entrepreneurs, artists and sports men and women for whom ADHD has been an integral part of their success.

These positive impacts are:

- Creativity

- Hyper-focusing skills

- Persistence

- Reactivity

- Lateral thinking

- Sensitivity to others

A recent World Health Organisation series of studies on ADHD included gathering opinions both on ability and disability concepts from ADHD experts as well as individuals diagnosed with ADHD, self advocates, immediate family members and professional caregivers.

These studies were carried out to develop an International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health Care sets for ADHD across all age ranges.

They are designed to be used in conjunction with the International Classification of Diseases (ICD).

The aim is that the description of functional categories in the ICF will create a common language that can be used by professionals from various disciplines to facilitate effective communication in the assessment and treatment of conditions.

One study involved experts in ADHD of whom 93% indicated positive attributes of ADHD.

These included a high level of energy, flexibility, resilience, perseverance, creativity and a generally optimistic attitude.

Individuals with ADHD were described as having a strong drive for things that interest and motivate them. They had an ability to inspire and energise those around them. They were fast learners, fast thinkers, fast decision makers and unafraid to take risks. Equally, they were described as sociable, caring and sensitive to others (Schiffer 2015).

Likewise, in the study involving people with ADHD and their families, 71% indicated positive sides to ADHD.

Strengths reported were high energy and drive function making it easier to engage in physical exercises such as sporting activities and to achieve personal goals.

Creativity was reported and, in particular, an ability to think “outside the box”. Hyper-focusing was considered a strength but depended on the activity being of interest to the individual. In addition, personal attributes such as agreeableness and willingness to work with others were regularly described (Mahdi 2017).

It is striking that the same positive attributes were indicated by individuals with ADHD, their families and by ADHD experts.

There is also evidence that adults with ADHD may use, often without recognition, skills and compensatory strategies to cope with symptoms prior to diagnosis and treatment (Canela 2017).

A study of 32 outpatient attenders in a speciality care center in a Swiss University Hospital identified five categories of compensatory strategies. They were organisational, motoric, attentional, social and psychopharmacological. Interestingly, some people considered their symptoms to be useful.

For instance, increased productivity as a consequence of organisational strategies used or being funny and entertaining in a crowd in some with hyperactivity who prefer crowds to 1:1 interactions because of their hyperactivity. These spontaneously generated coping skills are helpful, utilising the positive aspects of ADHD symptoms. They may also explain in part why so many are not diagnosed until well into adulthood.

However, a qualitative Irish study on the impact of ADHD in adults highlighted the importance of practitioners being aware of the perceived positive and negative impacts of ADHD on people’s lives. It also highlighted the need to be aware of the stigma associated with ADHD.

It emphasised the difficulties faced by those not receiving a diagnosis until adulthood, citing especially the sense of burden and impairment associated with ADHD symptoms, feeling different to other people., having missed opportunities all exacerbated by ADHD specific stigma not only in the general population but also among clinicians (Watters 2013).

Stigma and ADHD

Stigma is a recognised negative force in the lives of people with mental disorders and is associated with lower levels of employment, poorer access to housing, poorer self-esteem and the stress of having the disorder (Hinshaw 2008).

Not all mental disorders attract the same stigmatising attitudes (Sadler 2012). A developmental review of stigma in ADHD showed that these attitudes occurred at all ages with social rejection particularily evident. This type of stigma, the desire for social distance from people with ADHD, is equivalent to that experienced by people with depression (Lebowitz 2016).

A compounding factor has been stigmatisation by some adult mental health professionals in Europe, including in Ireland, in the form of the non-acceptance of ADHD as a valid diagnosis (Timini 2003, Kooij 2010, Carr-fanning 2015). This has occurred despite all the evidence to the contrary (Asherson 2005, Barkley 2002, Faraone 2006, Kooij 2010, for example).

Guiding Principles

The core values for this Clinical Programme are derived from the service user perspective and the evidence outlined in chapters 1-4 as well as contributions from other members of the Working Group and invited speakers

as listed below:

- Literature review

- Screening for ADHD symptoms in adults attending the Sligo/Leitrim adult mental health outpatient services

- Assessment and management of ADHD in Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services

- Assessment of adults with ADHD

- Treatment focused on empowerment

These core values require guiding principles or rules to ensure the development of a Model of Care based on these values. The principles provide the practical means of ensuring the core values, manifested as changes in attitude and behaviour with respect to service users, are built into the Model of Care. This, together with the core values of providing service users with access to skilled assessment and evidence-based treatment will ensure a timely, collaborative and recovery-focused service for adults with ADHD.

The ten principles on which this Model of Care is based are:

- Assessment and treatment of symptomatic ADHD in adults which causes significant functional impairment will be provided within the public mental health services.

- It will be based on AVFC and Sharing the Vision principles of multidisciplinary service delivery and joint working with the person to enable him/her to achieve the skills to manage the condition.

- Underpinning this will be the provision of training for mental health professionals in the diagnosis and treatment of ADHD.

- The recognition that many adults with ADHD who may be currently attending or have in the past attended the adult mental health services with, in particular, mood problems but also behavioural issues such as repeated self-harm (Asherson 2005) and this must be addressed.

- Collaborative working with adult mental health services, particularly general adult, will be essential.

- Additional resources will be required to deliver the recommended specific assessment format and interventions.

- Service provision will be based on mental health professionals having the requisite skills (following training) rather than being prescriptive about the number of each discipline required.

- The model of care will be developed to ensure geographic equity of access to assessment and treatment.

- Collaborative working with General Practice will be an essential feature.

- Integrated working across the health service and with non-health statutory and voluntary services will be a key component

These principles will underpin the design of the Clinical Programme as described in the following chapters.